Maximizing Throughput

Purpose

Adama's ability to execute many concurrent network calls is impaired due to the transactional boundary (and the historical roots in board games). This means a high latency third party service will dramatically block progress on a document, and large delays can introduce quadratic workloads (which is expensive for customers and slow).

Design Goals

The primary goal is to introduce a new way of modelling service invocations that are high performance enabling many concurrent invocations and operate at transaction-line-rate (the maximum commit rate to disk).

This induces a requirement that this new mechanism is going to live across two transactions: (i) the transaction that initiates a service method, and (ii) the transaction that represents the completion of the service method. Therefore, we take the burden that this will run at no more than half the transaction line rate.

Non Goals

The existing async system can be improved in a few ways, but these are considered nice to haves since asynchronous transactional memory is an extremely difficult problem. This document is focused purely on introducing a new way to do async calls.

7,500 foot view

We will introduce a new language primitive called "pipeline". The key idea is to create a queue of pending work that operates outside the document's main thread. The queue fundamentally needs to contain (1) the service name, (2) the method to invoke, (3) the calling principal, (4) the input message, (5) some closure context, and (6) a handler.

The closure context is important, so we will have a message type be used. For example,

message MyContext {

int user_id;

int invoice_id;

}

represents some context that is relevant the asynchronus call but not in the call. This context is useful for back pointers and connective ids that are passed from the caller to the handler. We will extend every existing service method to be a pipeline-capable invocation, and then the missing language primitive pipeline has a syntax of

pipeline<service::method> pipeline_name (MyContext context) {

// @request and @response are available

// @who is also available

}

This basic syntax provides the handler code such that:

(1) the bound service is identified to be extended,

(2) the method to invoke is identified,

(3) the calling principal is represented idiomatically as @who,

(4) the input message is available via the new @request constant,

(5) the output of the response is available via the new response constant,

and (6) the handler is the associated code.

Invocation then happens as an extension to the given service. For example,

pipeline<myphpservice::write> myownpipe (MyContext context) {

// do stuff

}

channel foo(SomeMessage m) {

myphpservice.myownpipe(

@who,

/* input */ {id:m.id},

/* context */ {user_id:m.user_id, invoice_id:42}});

}

Furthermore, this invocation provides sufficient information to enqueue the work.

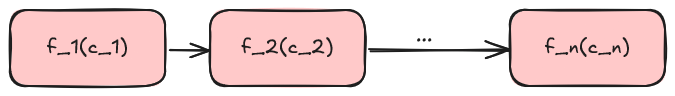

However, this work is limited to a linear topology:

So, we will some clarity on this may extend into more (a) complex call chain hierarchies. We also need to contend with (b) handling failures in a responsible way. (c) Operational safety is a prime concern since Adama plus a queue can be a denial of service attack provider if we don't handle this well.

Details

Complex call chains and rich topologies

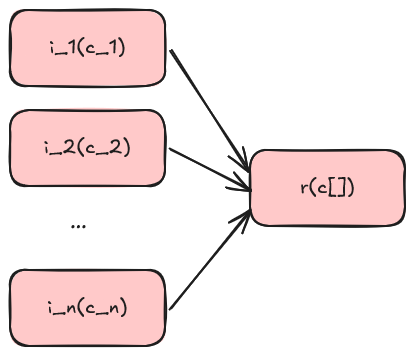

I suspect that the pareto-major case is introducing batching to allow for scatter and collect pattern ala:

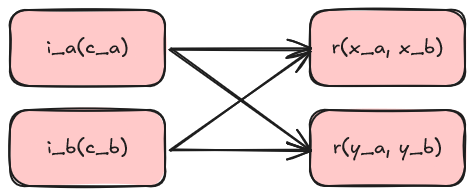

This happens when N requests are queued and then after those N things have processed, some code is ran. The pareto-minor case is also worth considering as it may be desirable to do some weaving where results feed into other methods.

This speaks to the need that the return from the pipeline invocation is some kind of future and work on futures can be queued up as well using a compute graph. Perhaps, we can introduce a new type of pipeline that doesn't operate on services.

pipeline<future<Response1>, future<Response2>[]>

future_pipe_method(MyContext c, Response1 r1, Response2[] r2) -> BatchResponse {

// do stuff on the futures

}

The invocation of future_pipe_method is then a traditional method invocation:

channel foo(Yo y) {

var f1 = service1.foo1(...)

var f2 = service2.foo2(...);

var fr = future_pipe_method({/*context*/}, f1, [f2]);

}

This code then is 100% synchronous in defining a computational graph of various transactions that (1) mutate the document, (2) build complex call chain hierarchies which execute in a predictable manner.

Handling failures

The proper way to contend with failures would be to make @response a maybe and introduce @failure constant.

Operational excellence

Since Adama owns the queue, it can coordinate with the service implementation to define the maximum number of inflight operations per machine and this can be further controlled using cross-machine gossip to rate limit service. This is, however, a broad topic.